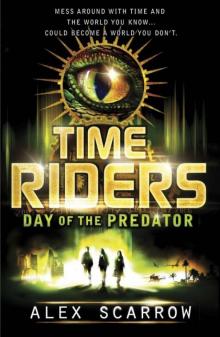

Day of the Predator

Day of the Predator Ellie Quin Book 3: Beneath the Neon Sky

Ellie Quin Book 3: Beneath the Neon Sky The Mayan Prophecy

The Mayan Prophecy October Skies

October Skies Ellie Quin Episode 4: Ellie Quin in WonderLand (The Ellie Quin Series)

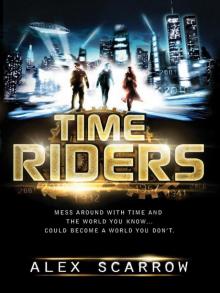

Ellie Quin Episode 4: Ellie Quin in WonderLand (The Ellie Quin Series) Time Riders

Time Riders Gates of Rome

Gates of Rome Reborn

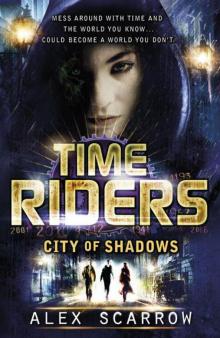

Reborn City of Shadows

City of Shadows Ellie Quin Book 2: The World According to Ellie Quin (The Ellie Quin Series)

Ellie Quin Book 2: The World According to Ellie Quin (The Ellie Quin Series) Ellie Quin Episode 5: A Girl Reborn

Ellie Quin Episode 5: A Girl Reborn Spore

Spore The Eternal War

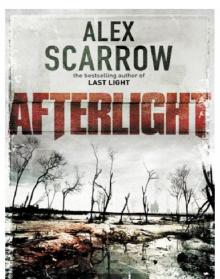

The Eternal War Last Light

Last Light Remade

Remade Ellie Quin Book 2: The World According to Ellie Quin

Ellie Quin Book 2: The World According to Ellie Quin Ellie Quin Book 3: Beneath the Neon Sky (The Ellie Quin Series)

Ellie Quin Book 3: Beneath the Neon Sky (The Ellie Quin Series) Plague World

Plague World Plague Nation

Plague Nation Ellie Quin Book 01: The Legend of Ellie Quin

Ellie Quin Book 01: The Legend of Ellie Quin Ellie Quin - 04 - Ellie Quin in WonderLand

Ellie Quin - 04 - Ellie Quin in WonderLand No Escape

No Escape TimeRiders

TimeRiders A Thousand Suns

A Thousand Suns The Candle Man

The Candle Man The Pirate Kings

The Pirate Kings Burning Truth: An Edge-0f-The-Seat British Crime Thriller (DCI BOYD CRIME THRILLERS Book3) (DCI BOYD CRIME SERIES)

Burning Truth: An Edge-0f-The-Seat British Crime Thriller (DCI BOYD CRIME THRILLERS Book3) (DCI BOYD CRIME SERIES) Day of the Predator tr-2

Day of the Predator tr-2 City of Shadows tr-6

City of Shadows tr-6 TimeRiders: The Infinity Cage (book 9)

TimeRiders: The Infinity Cage (book 9) The mayan prophecy (Timeriders # 8)

The mayan prophecy (Timeriders # 8) TimeRiders: The Doomsday Code (Book 3)

TimeRiders: The Doomsday Code (Book 3) Gates of Rome tr-5

Gates of Rome tr-5 TimeRiders: The Pirate Kings (Book 7)

TimeRiders: The Pirate Kings (Book 7) TimeRiders: The Mayan Prophecy (Book 8)

TimeRiders: The Mayan Prophecy (Book 8) TimeRiders 05 - Gates of Rome

TimeRiders 05 - Gates of Rome The Doomsday Code tr-3

The Doomsday Code tr-3 The Eternal War tr-4

The Eternal War tr-4 TimeRiders: City of Shadows (Book 6)

TimeRiders: City of Shadows (Book 6) Time Riders tr-1

Time Riders tr-1 Afterlight

Afterlight TimeRiders, Day of the Predator

TimeRiders, Day of the Predator Plague Land Series, Book 1

Plague Land Series, Book 1